Ever wondered how our team are activated to incidents? Here we take a behind-the-scenes look at our airdesk.

Jordan Parker, is one of three HEMS dispatchers, whose role is to monitor 999 calls to identify which patients are in most need of GNAAS’ help.

Prior to joining our charity, he spent three years with the North East Ambulance Service (NEAS) as a communications support officer and was heavily featured in the BBC’s latest series of Ambulance.

We had a chat with Jordan to find out more about the airdesk and how our team are tasked to incidents.

The airdesk has a lot of screens. What do you monitor on them?

From our airdesk we monitor the 999 calls coming in to NEAS and the North West Ambulance Service (NWAS) from members of the public, as well as ongoing incidents involving the mountain rescue.

We watch the calls come in on the screen and we’re also able to listen to the calls in the North East.

How are the team tasked to an incident?

If we think there’s an incident our team should be going to, we can ask the call taker questions to try and get a little bit more information, which will help us decide if the team need to be dispatched.

As well as attending incidents in the North East and North West, we also cover North Yorkshire, the Scottish border, and the Isle of Man.

So if there’s any incidents that need our immediate tasking, then the relevant ambulance service will directly ring us, and we’ll dispatch quite quickly to them.

What types of incidents do our team typically get dispatched to?

The incidents our team tend to go to include road traffic collisions, industrial incidents, serious assaults, medical emergencies, such as people who have been fitting for a long time, as well as cardiac arrests.

Besides monitoring and listening in to calls, are there any other ways that can help decide whether you dispatch to an incident?

So as well as our immediate dispatch criteria, we’ve got ways of interrogating calls. So if we see a call such as road traffic collision, we can use a system called GoodSAM to help us establish the seriousness of the incident. GoodSAM sends a link to the person’s phone, who made the 999 call, and from that we can access their phone’s camera and get a live look at the nature and extent of injuries sustained by a patient.

This helps us decide whether our team need to be dispatched to the incident.

What happens after the team are dispatched to an incident?

So once a call comes in requesting our assistance, we activate the team. If they’re not in the office, we will press a buzzer that will make a noise and then they’ll come in quite quickly.

I’ll pass the grid reference to the paramedic and the pilot will then ring air traffic control and let them know that our aircraft will be taking off shortly.

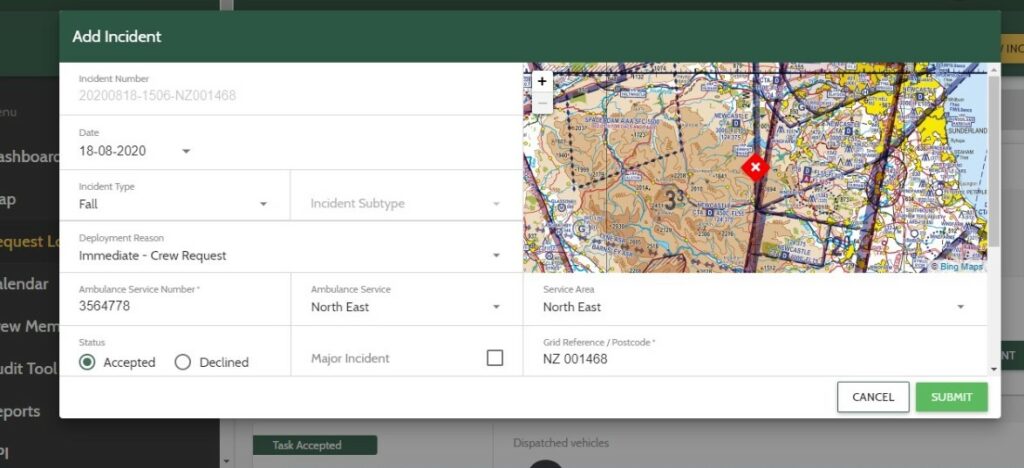

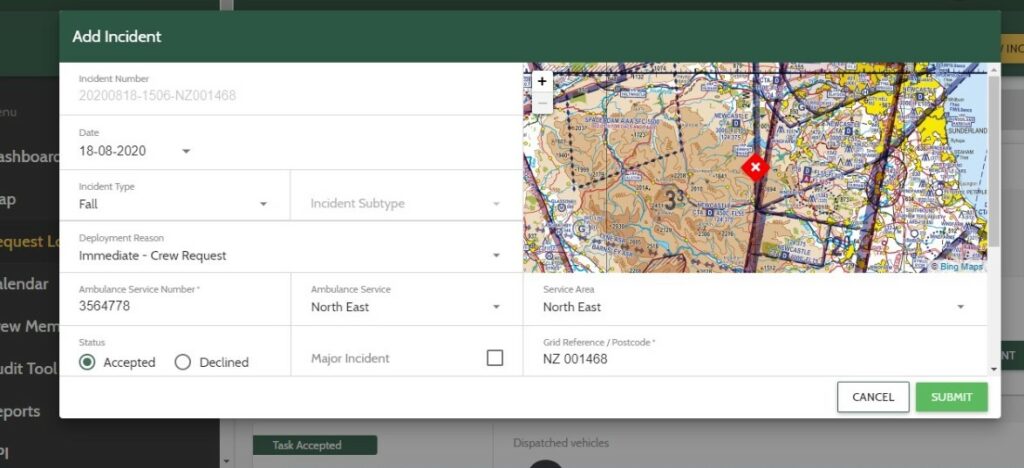

Once the team have left the base, I’ll log the incident on ARC, which is our system that we use to log all the incidents our team attend. The type of information I’ll add includes, where they’re going, the times of the incident, such as when they were tasked, when they left the base, when they arrived on scene (once they’ve got there) and a quick brief of what they’re going to.

We monitor them using two of our different tracking systems. One called airbox and one called spidertracks, so we can see exactly where they’re going.

If the helicopter will be going over Durham, I’ll ring the prison service because Durham’s a no fly zone, so we’ve got to get permission to fly in that area.

We’ll also ring the ambulance control room to let them know an ETA and obtain any additional information we need. If our team are going to be landing a short distance away from the actual scene, I’ll ask them to send someone to pick the team up.

I’ll also communicate with the team via radio and they will keep me updated about the incident. If the patient is going to be airlifted to hospital, I will pre-alert the relevant hospital and give them an ETA on when to expect our helicopter to arrive.